Picture a vast, sun-scorched landscape in the Niger Delta. Below the ground lies a sea of “black gold”—crude oil worth billions of dollars. Now, picture the communities living on that land: grappling with poverty, environmental degradation, and a lack of basic services. This stark contrast isn’t an anomaly; it’s a pattern repeated across the globe, from the diamond fields of Sierra Leone to the gas reserves of Central Asia. This is the heart of a fascinating and tragic geographical paradox known as the Resource Curse, or the Paradox of Plenty.

The core question is hauntingly simple: Why do countries blessed with immense natural resource wealth so often end up with struggling economies, rampant corruption, and even violent conflict? The answer lies at the complex intersection of economics, politics, and, crucially, geography.

The Dutch Disease: When a Strong Currency Makes a Nation Weaker

One of the primary economic mechanisms behind the resource curse has a surprisingly European name: “Dutch Disease.” The term was coined in the 1970s after the Netherlands discovered vast natural gas fields in the North Sea. The expected economic boom turned into something far more complicated.

Here’s how it typically unfolds:

- A Flood of Foreign Cash: A country begins exporting a valuable resource like oil or minerals. This brings in a massive influx of foreign currency (e.g., US dollars).

- Currency Appreciation: To use this money domestically, the country must convert it into its local currency. This huge demand for the local currency causes its value to skyrocket relative to other currencies.

- Other Exports Suffer: Suddenly, the country’s other export sectors, like agriculture or manufacturing, become uncompetitive. A farmer in Nigeria selling cocoa or a factory in Venezuela selling textiles finds their products are now far more expensive for foreign buyers, who can get them cheaper elsewhere. Their industries wither.

- Imports Become Cheaper: At the same time, the strong local currency makes imported goods incredibly cheap, further undercutting local producers.

The result is a national economy that becomes dangerously dependent on a single, volatile commodity. The diverse skills and industries that build a resilient, modern economy are hollowed out. The geographical concentration of the economy shifts from farms and factories spread across the country to a few specific mining or drilling locations, creating profound regional inequality.

The Political Geography of the “Honey Pot”

Perhaps even more damaging than the economic effects are the political ones. Abundant resource wealth acts like a giant “honey pot” for a nation’s elite, fundamentally warping the relationship between a government and its people—a core concept in human geography.

In most stable countries, governments rely on taxing their citizens to function. This creates a social contract: citizens pay taxes in exchange for services and representation. This accountability is the bedrock of democracy. But when a government can fund itself simply by selling oil or diamonds, it no longer needs to tax its population in the same way. It becomes a “rentier state”, living off unearned “rents” from its geography rather than the productive capacity of its people.

This disconnect has devastating consequences. With no need to answer to the public for its revenue, accountability evaporates. Corruption thrives as officials and elites vie for control of the resource wealth. Institutions like the judiciary and civil service, which are essential for fair governance, are often weakened or co-opted.

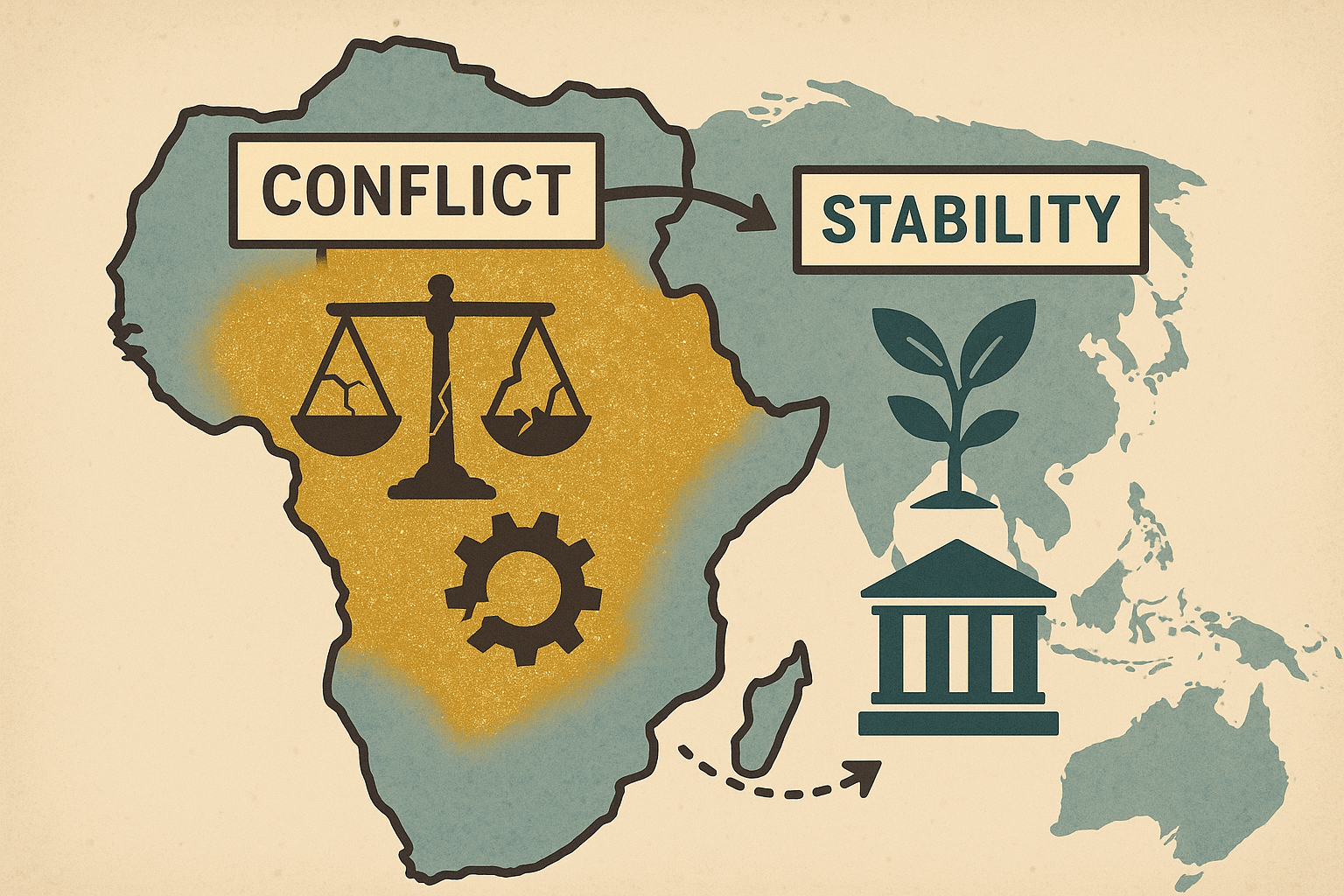

This dynamic can also fuel violent conflict. The immense prize of controlling a nation’s resources can be a powerful incentive for civil war. The term “blood diamonds” emerged from the brutal conflicts in Sierra Leone and Angola, where rebel groups fought for control of diamond-rich territories, using the gems to fund their wars. The physical geography of the resources—often located in remote, marginalized regions—can further exacerbate tensions and fuel secessionist movements, as seen with the oil-rich Cabinda exclave in Angola.

Riding the Commodity Rollercoaster

A final piece of the curse is volatility. The prices of commodities like oil, copper, and gas are notoriously unstable, swinging wildly based on global supply, demand, and geopolitical events. For a country whose entire budget depends on these prices, the result is a perpetual boom-and-bust cycle.

During a boom, when prices are high, governments often embark on lavish spending sprees. They build grandiose infrastructure projects, heavily subsidize fuel and food, and bloat the public sector payroll. There is little incentive to save or diversify the economy.

But when the inevitable bust arrives and prices crash, the national income plummets. Governments are left with massive debts, unfinished “white elephant” projects, and a population accustomed to subsidies that are no longer affordable. This leads to painful austerity measures, social unrest, and economic collapse. Cities that boomed overnight can become ghost towns just as quickly. Venezuela, home to the world’s largest oil reserves, provides a tragic modern example of this devastating cycle.

Is the Curse Inevitable? Beating the Paradox

Fortunately, geography is not destiny. The resource curse is a powerful tendency, not an iron law. Several countries have successfully managed their natural wealth, turning a potential curse into a genuine blessing. Their success stories show that governance is the critical variable.

Norway is the textbook example. When it discovered vast North Sea oil reserves, its strong, pre-existing democratic institutions were crucial. Instead of spending the windfall, Norway funneled its oil revenues into the world’s largest sovereign wealth fund, now worth over $1 trillion. This fund invests abroad to avoid causing Dutch Disease and saves the wealth for future generations. The process is transparent, and the national debate is about how to best manage the funds, not who gets to steal them.

Another, perhaps more surprising, example is Botswana. Despite being a landlocked African nation, it has used its immense diamond wealth to achieve one of the continent’s highest rates of economic growth and stability. Prudent fiscal policy, low levels of corruption, and consistent investment in public goods like healthcare and education allowed it to avoid the pitfalls that befell its neighbors.

The lesson from these nations is clear: natural resources themselves are not the problem. The curse takes hold when the wealth flows into a context of weak governance, fragile institutions, and a lack of foresight. The true wealth of a nation isn’t buried in its ground—it’s found in the strength of its institutions and the well-being of its people.