For decades, the story of climate change has been one of retreat and loss. We see images of shorelines swallowed by rising seas, farmlands baked into deserts, and communities scattered by superstorms. But a parallel story is quietly unfolding, one not of retreat, but of relocation. As some parts of our planet become less hospitable, others are emerging as potential sanctuaries. Welcome to the era of the “climate haven”—a new kind of boomtown shaped not by gold rushes or oil strikes, but by the promise of a more stable future.

Mapping the Havens: The Geography of Climate Resilience

What makes a city a potential climate haven? The answer lies in a combination of favorable physical and human geography. While no place will be entirely immune to the effects of a warming planet, some are geographically positioned to weather the storms, literal and figurative, far better than others.

The key ingredients for a climate-resilient city often include:

- Abundant Freshwater: As droughts intensify globally, reliable access to freshwater is paramount. Locations near large, stable bodies of freshwater have a distinct advantage.

- Cooler Temperatures: Cities in northern latitudes are less likely to experience the life-threatening, multi-day heatwaves projected for southern regions. Their cooler baseline means that even with warming, summers remain manageable.

- Protection from Sea-Level Rise: Coastal cities from Miami to Jakarta are on the front lines of rising oceans. In contrast, inland cities, particularly those at higher elevations, are naturally insulated from this specific threat.

- Lower Risk of Catastrophic Events: While no region is without risk, some are less prone to the mega-wildfires, devastating hurricanes, or widespread water scarcity that will define other areas.

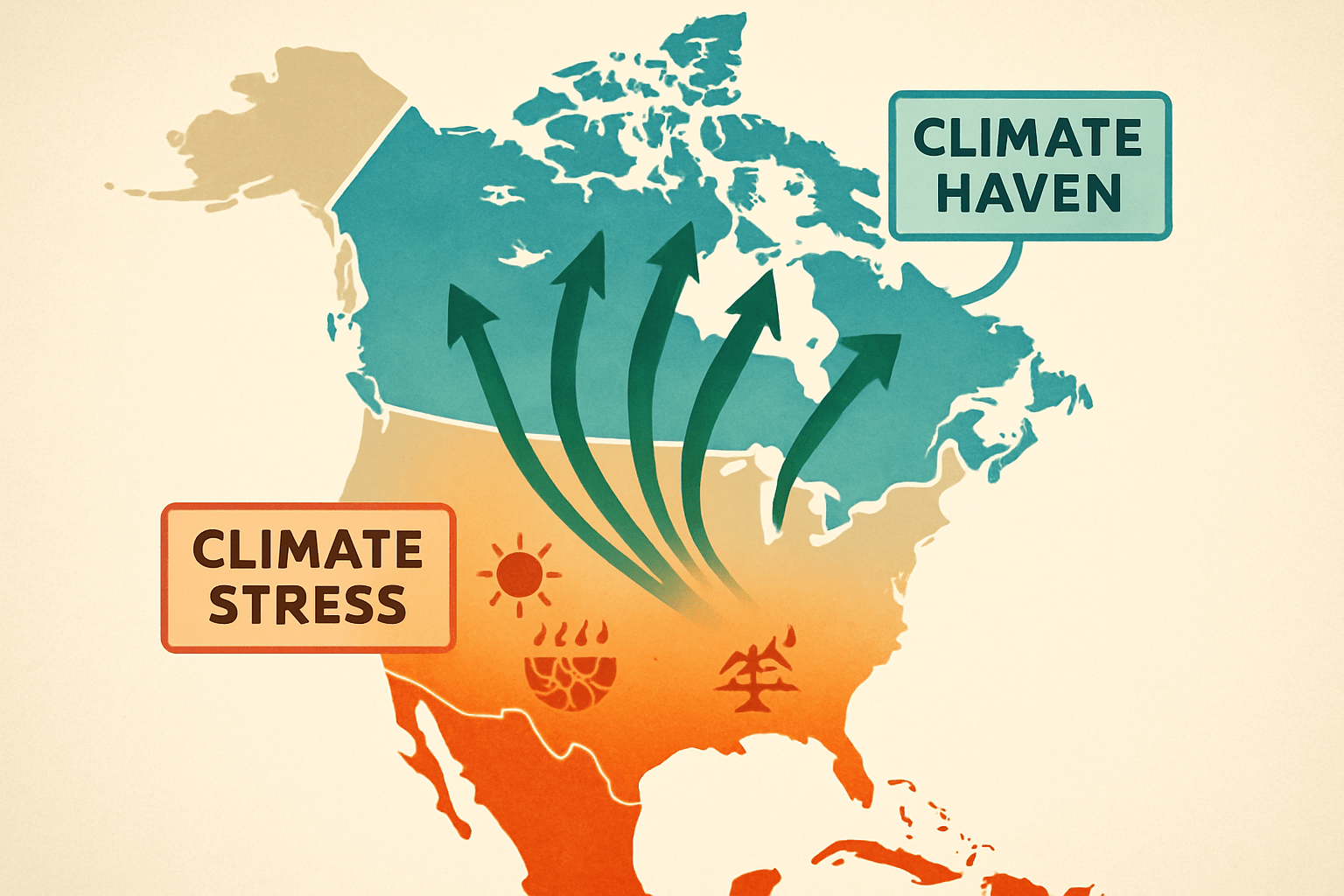

When you overlay these factors on a map, a few key regions light up. The most cited example is North America’s Great Lakes region. Cities like Duluth, Minnesota; Buffalo, New York; and Toronto, Ontario, are increasingly discussed as prime candidates. They sit beside the largest freshwater system on Earth, have temperate climates, and are far from the reach of rising tides. Buffalo, once a symbol of post-industrial decline, is now rebranding itself as a “climate refuge city”, actively welcoming new residents seeking stability.

Beyond the Great Lakes, other potential havens emerge. Inland cities in the Pacific Northwest, like Boise, Idaho, offer cooler climates, though they must still contend with regional wildfire smoke. Across the Atlantic, Northern European cities in Scandinavia and the Baltic states—known for their forward-thinking urban planning and cooler climates—are also seen as resilient destinations.

The Human Geography of a Shifting Population

The rise of these havens is fundamentally a story of human geography—the study of how people and their environments interact. We are witnessing the beginnings of a great internal reshuffling, a form of climate migration that differs from the desperate flight of refugees. This is often a slower, more deliberate migration, undertaken by those with the resources to choose where they live.

As professionals, families, and retirees look at a 30-year mortgage, they are starting to factor in 30-year climate projections. Will their home be insurable? Will there be water? Will it be safe? This calculus is already driving a “slow-motion migration” away from vulnerable Sun Belt states like Arizona and Florida towards the perceived safety of places like Vermont, Michigan, and the Pacific Northwest.

This influx can inject new life into cities that have experienced population decline. It can spur economic growth, diversify the job market, and bring new investment. For a city like Buffalo, the narrative shift from “Rust Belt” to “Climate Belt” is a powerful engine for revitalization. But this optimistic picture has a dark and complicated underside.

The Ethical Compass: Navigating Climate Gentrification

The concept of a “haven” implies sanctuary for all, but the reality could be far more exclusionary. The migration to climate-resilient cities raises profound ethical dilemmas, chief among them a phenomenon known as “climate gentrification.”

When affluent newcomers, often able to pay cash for homes, move into a climate haven, they drive up demand for housing. Real estate prices soar, and rental markets tighten. This can displace long-term, often lower-income residents who suddenly find themselves priced out of the very communities they have called home for generations. In this scenario, climate resilience becomes a luxury good, a commodity available only to those who can afford the price of admission.

This creates a deeply uncomfortable geography of inequality. Who gets a spot in the “lifeboat”? If cities like Duluth or Madison become magnets for the wealthy, what happens to the residents of Phoenix or Houston who lack the means to move? The rise of the climate haven forces us to confront difficult questions:

- Is there a municipal responsibility to ensure housing remains affordable for existing residents?

- How can cities manage the immense strain on infrastructure—water systems, power grids, schools, and healthcare—that a population boom will bring?

- What do we owe the communities being left behind in increasingly volatile regions?

Planning for the Influx: Proactive vs. Reactive Urbanism

The future of climate haven cities hinges on their ability to plan proactively rather than reactively. A city that simply allows market forces to run their course risks exacerbating inequality and social friction. A city that plans for an equitable future can turn this challenge into an opportunity.

Proactive strategies are already being discussed and, in some cases, implemented. These include:

- Updating Zoning Codes: Encouraging the development of denser, more diverse housing options, including affordable and “missing middle” housing like duplexes and townhomes.

- Investing in Infrastructure: Upgrading public transit, expanding water treatment facilities, and investing in green infrastructure to manage stormwater and create resilient public spaces.

- Centering Equity: Creating policies like inclusionary zoning, community land trusts, and property tax relief for long-term residents to protect them from displacement.

The conversation is no longer theoretical. It’s a present-day challenge in urban planning and governance. The decisions made today in city halls from the Great Lakes to Scandinavia will determine whether these havens become inclusive sanctuaries or exclusive enclaves.

Ultimately, the rise of the climate haven is one of the most compelling geographic stories of our time. It’s a tangible manifestation of how climate change is redrawing our maps—not just the physical maps of coastlines and ecosystems, but the human maps of where and how we live. These cities are a test case for our collective ability to adapt, not just to a changing environment, but to the profound social and ethical questions that come with it.