Have you ever been driving down the motorway, glancing at road signs, and noticed a pattern? Manchester, Winchester, Leicester. Or maybe it’s the trio of Southampton, Northampton, and Sutton. These aren’t just random sounds; they are living fossils, echoes of history embedded in the landscape. The names of our towns and cities are a secret code, and once you learn the language, you can read the story of a place just by looking at its name on a map.

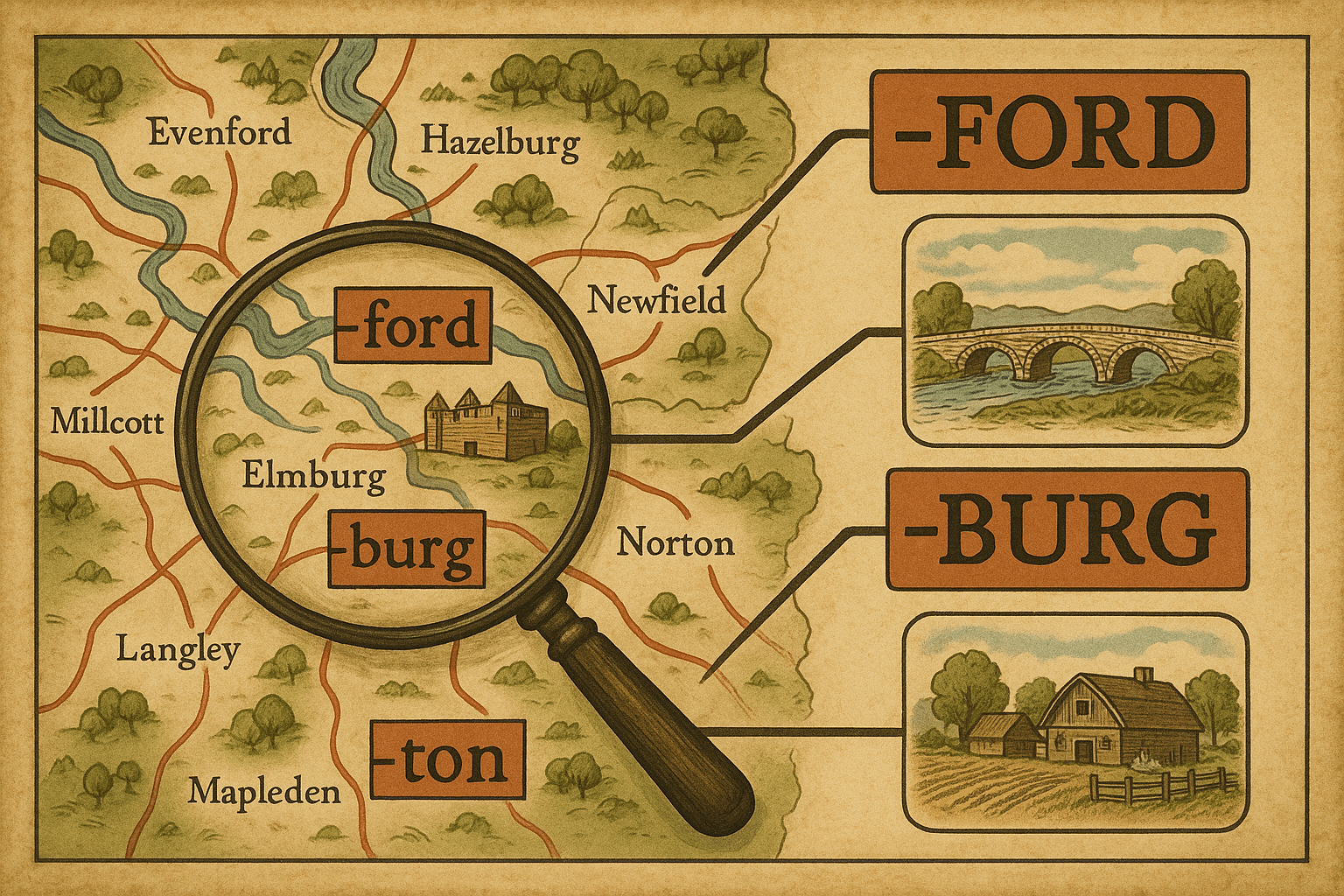

This hidden language is the focus of toponymy, the study of place names. Every -ton, -ford, and -by is a clue, a breadcrumb left by Romans, Anglo-Saxons, or Vikings. They tell us about the geography of a place, the people who founded it, and the long, layered history of the land itself. Let’s become toponymy detectives and start decoding.

The Roman Imprint: Forts and Roads

Our story begins nearly 2,000 years ago. When the Romans conquered Britannia, they were master engineers and soldiers, and they left their mark in the most practical way possible: with forts and roads. The Latin word for a fortified camp was castrum.

As the Roman Empire faded and Anglo-Saxons moved in, they didn’t always know what these strange, stone-walled ruins were, but they knew they were old and fortified. They adapted the Latin word into their own Old English, and castrum became ceaster. This single word is the ancestor of some of the most common place name endings in England:

- -chester: The most direct translation, as seen in Manchester and Winchester.

- -caster: A northern variation, found in Lancaster and Doncaster.

- -cester: A softened, subtler version, as in Leicester and Gloucester (often pronounced ‘-ster’).

So, the next time you see one of these endings, you know you’re looking at a place that was once a Roman military stronghold—the very foundation of England’s urban geography.

The Anglo-Saxon Foundation: Building a Nation

After the Romans left, the Anglo-Saxons became the primary architects of England’s settlements. Their language, Old English, is the source of the vast majority of our place names. They named places based on who lived there, what they did, and what the land looked like. They were farmers, families, and pioneers, and their names reflect that.

Settlements and People

The most common place name element in England is -ton. It comes from the Old English tūn, which originally meant “enclosure” or “fence”, but quickly came to mean a farmstead, estate, or village. From Sutton (“south farm”) to Kingston (“the king’s estate”), it’s a sign of a fundamental Anglo-Saxon settlement.

A close cousin is -ham, meaning “homestead” or “village.” Think of Birmingham (the homestead of Beorma’s people) or Nottingham (the homestead of Snot’s people—yes, really!).

To understand who “Beorma’s people” were, you need to look for another key element: -ing. This suffix means “the people of” or “the followers of.” Reading means “[the place of] Rēada’s people”, and Hastings is “[the place of] Hæsta’s people.” It gives the town a tribal, almost familial, origin story.

Another common sign of a fortified settlement is -bury or -borough, from the Old English burh, meaning “a fortified place.” This was the Anglo-Saxon equivalent of a fort or defensive town, like Canterbury (“the fort of the people of Kent”).

Reading the Natural Landscape

The Anglo-Saxons also named places for their physical features. These are some of the most evocative names, painting a picture of what the land looked like 1,500 years ago.

- -ley or -leigh: From lēah, meaning a clearing in a forest. Crawley means “a clearing full of crows.” It tells you the area was once heavily wooded.

- -ford: A shallow river crossing. This is a perfect example of human and physical geography combined. Oxford is literally where oxen forded the river, and Stratford is where a Roman road (stræt) crossed a river.

- -den: A wooded valley, often used for pasture (especially for pigs). Think of Tenterden.

- -hurst: A wooded hill.

- -ey: Means “island”. It can refer to a true island or, more often, a patch of dry land in a marsh or fen. Ely in Cambridgeshire means “the isle of eels”, pointing to its history in the marshy Fens.

The Viking Echo: Scandinavian Takeover

In the 9th and 10th centuries, a new wave of people arrived: the Vikings. They conquered and settled a vast swathe of northern and eastern England, an area that came to be known as the Danelaw. Their language, Old Norse, splashed a whole new set of words across the map.

You can trace the borders of the Danelaw just by looking for Viking place names. The most definitive is -by, from the Old Norse býr, meaning “farmstead” or “village.” It’s the Scandinavian equivalent of -ton. Places like Grimsby (“Grim’s village”) and Whitby (“white village”) are tell-tale signs of Viking heritage.

Other key Viking markers include:

- -thorpe: An outlying farmstead or a secondary settlement, often built on the edge of a more established village. See Scunthorpe.

- -thwaite: A clearing or meadow. It’s the Norse version of the Anglo-Saxon -ley. You’ll find it all over the Lake District, as in Braithwaite (“broad clearing”).

- -toft: A homestead or the site of a house.

Putting It All Together: Be a Local Detective

Now you have the keys to the code. Look at a map of your own area. What do you see?

Let’s take Birmingham. We can break it down: Beorma + ing + ham. Beorma was likely an Anglo-Saxon chieftain. The “-ing-” tells us we’re talking about his people, his tribe, or his family. And “-ham” means homestead. So, Birmingham is “the homestead of the people of Beorma.” It’s a personal story, a pin dropped on a map marking the home of a specific clan.

Or look at Derby. Djúr (Old Norse for “deer”) + býr (Old Norse for “village”). It simply means “deer village”—a name that instantly conjures an image of its wild, pastoral origins.

The names you see every day are not just labels. They are a time capsule. They reveal layers of migration and conquest, of ancient forests and forgotten river crossings. They are a testament to the people who first cleared the land, built a fence, and called it home. So, next time you’re on a journey, pay attention to the signs. They’re telling you the secret story of the landscape. What does your town’s name say about its past?