Walk into any pub from the rolling hills of Dorset to the misty glens of the Scottish Highlands and ask a simple question: “Is England a country?” You’ll likely get a firm “Of course!” Ask the same about Scotland, and you’ll receive an equally resolute nod. Yet, look at a world map, and you’ll find one single entity: The United Kingdom.

It’s one of the most common and confounding puzzles in geography. How can a single sovereign state be composed of multiple countries? The answer lies in a unique blend of history, politics, and a fiercely protected sense of identity. Let’s solve the puzzle of the UK.

First, The Simple Bit: The Sovereign State

On the international stage, the answer is straightforward. The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland (the UK) is a sovereign state. It’s the entity that holds a seat at the United Nations, is a member of NATO, and acts as a single political body in global affairs. When we talk about a “country” in the sense of an independent, self-governing nation-state, the UK is the correct answer.

But that’s where the simplicity ends. To understand the UK, you have to look inside its borders, where the story becomes far richer and more complex.

A Union of Nations: The ‘Constituent Countries’

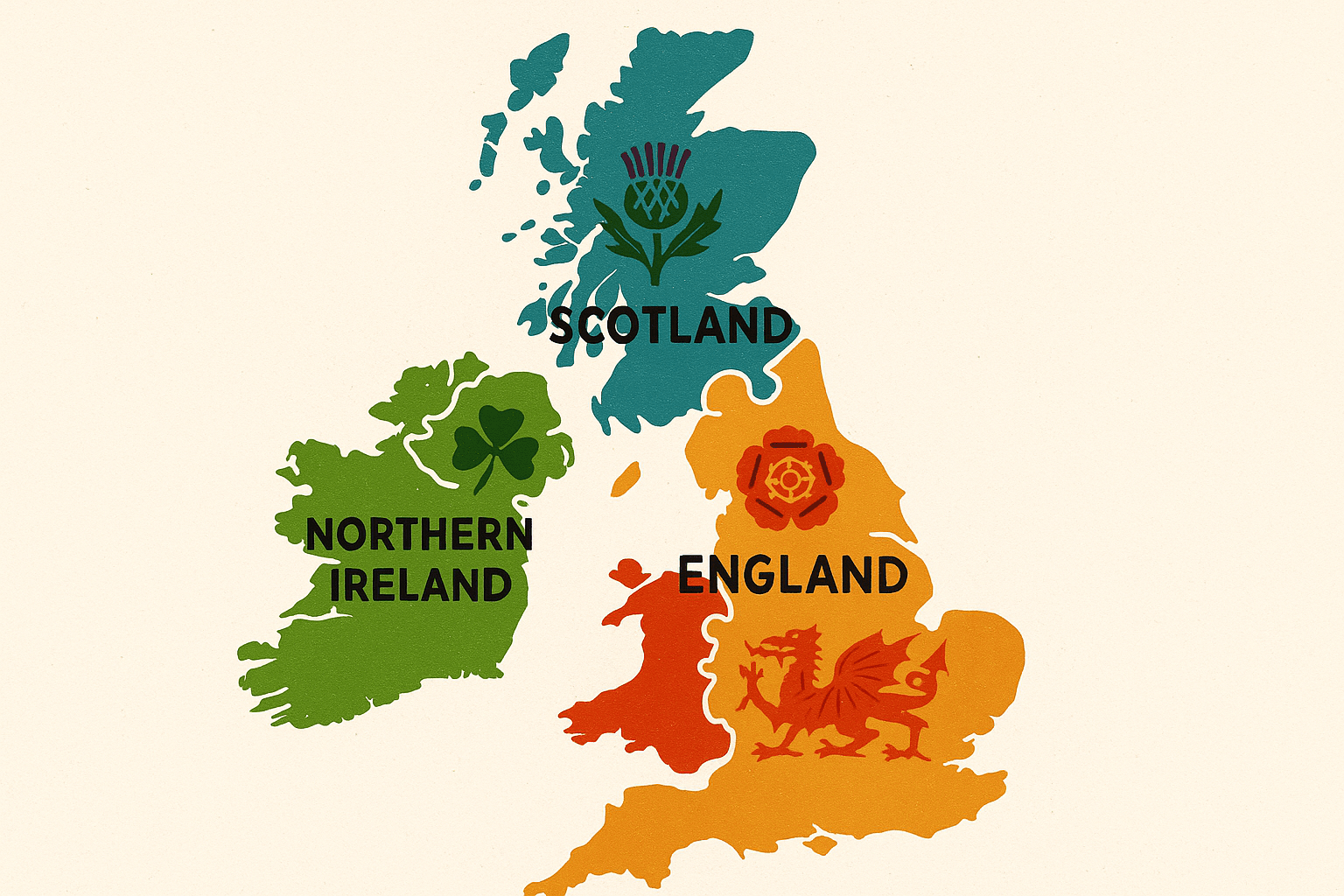

The UK is best understood not as a single, homogenous nation, but as a political union of four distinct parts: England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland. These are officially and commonly referred to as the UK’s “constituent countries” or “home nations.”

Think of it as a country made of countries. Each one possesses a unique history long predating the formation of the United Kingdom. They weren’t simply administrative regions created for convenience; they were, for much of their history, separate kingdoms and principalities that came together—sometimes willingly, sometimes not—over centuries.

- The Kingdom of England, the largest and most populous, formally united with Wales through the Acts of Union in 1536 and 1542.

- The Kingdom of Scotland, a historic rival, joined with England in a political union in 1707 to form the Kingdom of Great Britain. This was a union of crowns and parliaments, not a conquest, a crucial distinction that underpins Scottish identity today.

- Ireland was incorporated in 1801, creating the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. Following the Irish War of Independence, the island was partitioned in 1921, with Northern Ireland remaining part of the UK.

This historical journey is why these national identities remain so incredibly potent. People from Scotland don’t just say they’re “British”; they are Scottish. The same is true for the Welsh, English, and Northern Irish.

A Land of Geographical Contrasts

The distinctiveness of the home nations is carved into the very landscape. The geography of the UK is not uniform; it’s a patchwork of dramatically different environments that reinforce these separate identities.

Physical Geography

Travel from south to north and you’ll witness a stunning transformation. England is characterized by its gentle, low-lying terrain: the rolling Cotswold Hills, the flat and fertile Fens of East Anglia, and the major river systems of the Thames and Severn. Its uplands, like the Pennines and the fells of the Lake District, are rugged but rarely reach the dramatic heights seen elsewhere.

Cross the border into Scotland, and the landscape erupts. This is a land of mountains (munros), deep valleys (glens), and vast, moody lakes (lochs). The Scottish Highlands are an ancient, weathered mountain range that contains Ben Nevis, the highest point in the entire British Isles. The nation’s geography is further defined by its hundreds of islands, from the Inner and Outer Hebrides to Orkney and Shetland in the far north.

To the west, Wales (Cymru) is a nation defined by its mountains. The formidable peaks of Snowdonia National Park and the sweeping plateaus of the Brecon Beacons form a mountainous spine down the country, bordered by a famously rugged and beautiful coastline. In Northern Ireland, the landscape is shaped by the vast Lough Neagh—the largest freshwater lake in the British Isles—and the rolling hills of counties Antrim and Down, culminating in the unique basalt columns of the Giant’s Causeway.

Human Geography and Cities

Population and urban life also follow different patterns. England is by far the most populous country, with a density concentrated around London, a sprawling global megacity that serves as the UK’s political and economic capital. Other major English urban centres include Manchester, Birmingham, and Liverpool, each with a powerful industrial and cultural heritage.

Scotland’s population is concentrated in its Central Belt, between its historic, stately capital, Edinburgh, and its larger, industrious heartland, Glasgow. In Wales, the population is skewed to the south, around the capital, Cardiff, and nearby Swansea. Northern Ireland’s hub is its capital, Belfast, a city reborn from its troubled past into a vibrant cultural centre.

A Tapestry of Language and Culture

More than just geography and history, it is culture that provides the most compelling evidence for England, Scotland, and the others as distinct countries.

Language: While English is ubiquitous, it is far from the only native tongue. The UK has a rich linguistic heritage rooted in Celtic languages:

- Welsh (Cymraeg) is a thriving language, an official language in Wales, and a major success story of language revitalisation. You’ll see it on road signs, hear it in schools, and watch it on TV channel S4C.

- Scottish Gaelic (Gàidhlig) is spoken mainly in the Highlands and Islands, and its heritage is proudly displayed on bilingual signs throughout the region.

- Scots, a Germanic language related to English (not a dialect!), is widely spoken in the Scottish Lowlands.

- Irish (Gaeilge) has official recognition in Northern Ireland.

Distinct Institutions: The differences are hard-wired into the UK’s structure. Scotland has its own legal system (Scots Law), a separate education system, and its own national church. This institutional separation is a powerful marker of nationhood.

Sport: For many, the most visible proof is on the playing field. In football (soccer), rugby, and the Commonwealth Games, England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland compete as proud, separate nations, often against each other in fierce rivalries.

The Modern Puzzle: Devolution

In recent decades, the political structure has evolved to reflect these separate identities. Through a process called devolution, power has been transferred from the central UK Parliament in Westminster to legislative bodies in three of the four countries:

- The Scottish Parliament in Holyrood, Edinburgh.

- The Welsh Parliament (Senedd Cymru) in Cardiff.

- The Northern Ireland Assembly at Stormont, Belfast.

These devolved governments have powers over significant areas like health, education, and transport. England is the exception, as it has no devolved parliament of its own; English affairs are handled by the UK Parliament.

The Verdict: A Country of Countries

So, are England and Scotland countries? The answer is an emphatic yes.

They are not sovereign states, but they are countries in every other meaningful sense: historically, culturally, geographically, and, increasingly, politically. The UK’s unique genius—and its greatest challenge—is in holding these ancient national identities together within a single, modern state. It is a puzzle, but one whose complexity is part of its enduring fascination. The United Kingdom isn’t just a name on a map; it’s a living, breathing family of four distinct nations sharing a single island story.