The Rhythm of the Mountains: What is Transhumance?

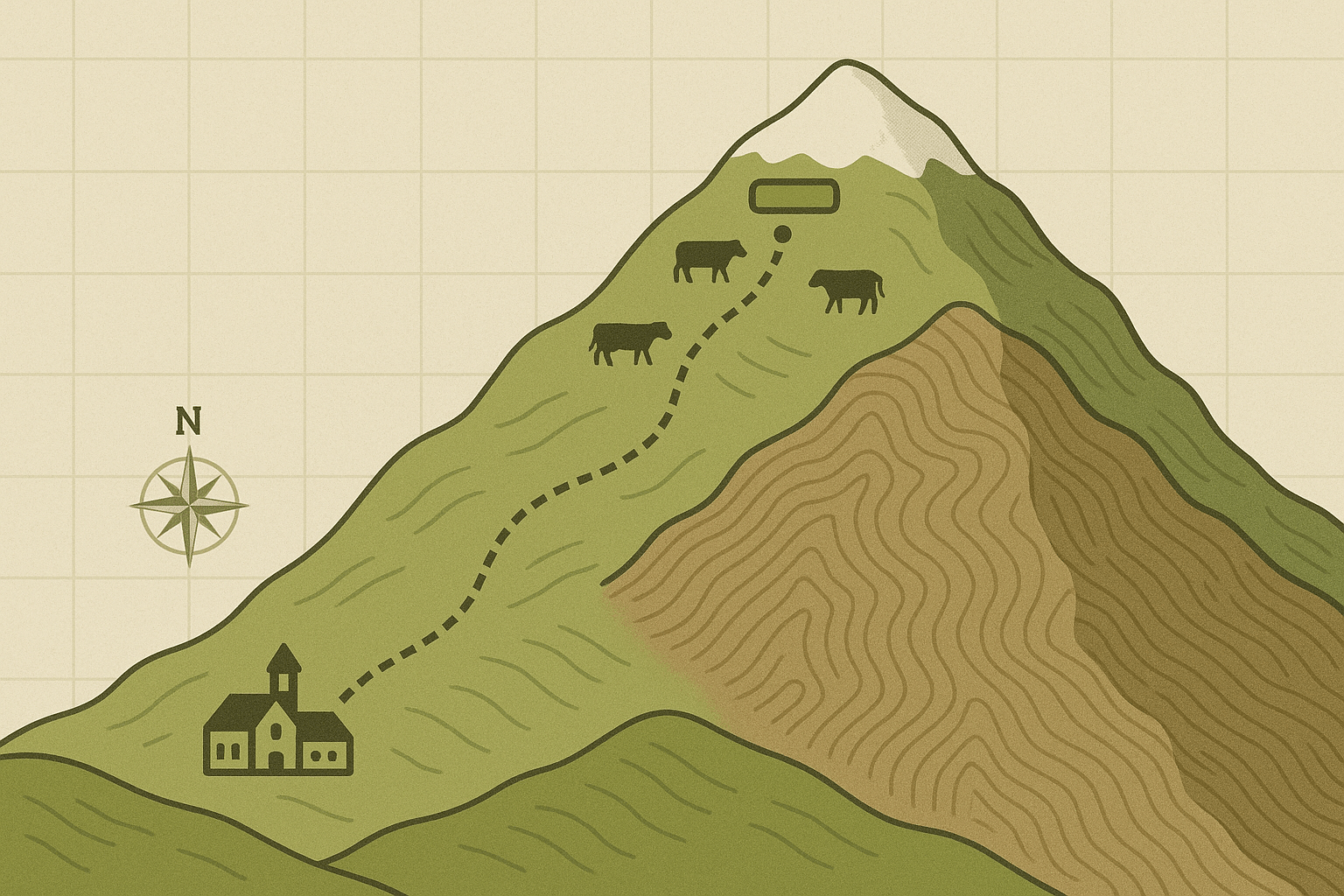

At its core, transhumance is a form of pastoralism defined by the seasonal movement of livestock. It is a profoundly geographical phenomenon, a dance dictated by altitude, climate, and topography. As snow blankets the high peaks in winter, rendering them inhospitable, herders guide their cattle, sheep, and goats down to the relative safety and shelter of the lowland valleys. Come spring, as the snow recedes and reveals lush, green pastures, the journey is reversed. The animals ascend to the high-altitude meadows, known as alpages in French, almen in German, or alpeggi in Italian, to graze for the summer months.

This vertical migration is not a casual stroll. It is a carefully planned exodus that follows ancient routes, crossing mountain passes and navigating steep terrain. It is a practice born of necessity that has, over millennia, carved paths, cultures, and entire economies into the alpine landscape.

A Geographical Necessity: Carving Life from Rock and Ice

The Alps, stretching across eight countries, are a formidable barrier of rock and ice. Their physical geography is one of dramatic verticality, where climate and vegetation change drastically over just a few hundred metres of elevation. This vertical world is the engine of transhumance.

Vertical Landscapes

In winter, the high pastures are buried under metres of snow, and temperatures plummet far below freezing. Survival is impossible. Meanwhile, the valley floors, while safer, have limited grazing land, much of which is needed to grow hay for winter fodder or other crops. Summer flips this dynamic. The valleys can become hot and their pastures depleted, while the high mountains burst into life. The melting snows water a carpet of nutrient-rich grasses and wildflowers, creating a perfect, if temporary, paradise for grazing animals. This geographical duality—uninhabitable highlands in winter, resource-rich highlands in summer—makes seasonal migration the most logical and sustainable way to raise livestock.

The Human Footprint

This movement has profoundly shaped the human geography of the Alps. It has influenced settlement patterns, with permanent villages in the valleys and temporary stone huts and dairies built high in the alpages. More importantly, transhumance is a form of landscape architecture. The constant grazing of livestock prevents the natural succession of forests, maintaining the open, biodiverse meadows that are now considered a quintessential feature of the alpine scenery. Without the herds, many of these iconic vistas would simply disappear under a blanket of shrubs and trees.

A Tapestry of Traditions: Transhumance Across Alpine Nations

While the principle is the same, the culture and character of transhumance vary wonderfully across the alpine nations of Switzerland, France, and Italy.

Switzerland: The Land of Cheese and Cowbells

In Switzerland, the seasonal ascent (Alpaufzug) and, more famously, the descent (Alpabzug or Désalpe) are deeply ingrained in the national identity. In regions like Gruyère, Appenzell, or the Emmental, the return of the herds is a major festival. The lead cows are adorned with enormous, ornate bells (trycheln) and elaborate floral headdresses. This tradition is directly linked to Switzerland’s most famous export: cheese. The rich, complex flavours of cheeses like Gruyère AOP or Appenzeller are attributed to the diverse alpine flora the cows consume on the high pastures. The cheesemaker often moves up to the mountains with the herd, transforming the milk into wheels of cheese in high-altitude dairies—a perfect example of geography shaping gastronomy.

France: Following the Ancient Drailles

In the French Alps, particularly in regions like Provence and the Savoie, the Transhumance often involves vast flocks of sheep. For centuries, they have migrated from the hot, dry plains of the Crau in Provence to the cooler mountains of the Southern Alps. They travel along ancient drove roads known as drailles. These grassy tracks, worn into the landscape by millions of hooves, are a tangible link to the past. While some routes are now paved roads, requiring herders to navigate modern traffic, many remote drailles still guide the flocks through stunning landscapes, passing through villages that celebrate their arrival and departure.

Italy: A Cross-Border Heritage

From the Aosta Valley to the Dolomites, the Italian Transumanza is a cornerstone of mountain life, a practice so vital it was inscribed on UNESCO’s list of Intangible Cultural Heritage. One of the most breathtaking examples occurs on the border of Italy and Austria. For over 600 years, shepherds from the Schnalstal (Val Senales) in Italy’s South Tyrol have guided thousands of sheep across glaciated, 3,000-metre-high passes like the Hochjoch into the Ötztal valley of Austria. This arduous two-day journey is one of the last remaining cross-border transhumance treks in the Alps, a powerful testament to a time when cultural and economic ties flowed freely across mountain passes, long before modern borders were drawn.

The Path Forward: Modern Transhumance in a Changing World

Today, this ancient practice faces modern challenges. EU regulations, agricultural industrialisation, rural depopulation, and conflicts with new predators like the returning wolf all place pressure on herders. The old routes are sometimes bisected by highways and railways, and the younger generation is often drawn to less arduous professions.

Yet, transhumance endures. There is a growing appreciation for its benefits: it produces high-quality, artisanal products like alpine cheese and meat; it is a model of sustainable land management; and it is a powerful source of cultural identity and tourism. The vibrant festivals of the Désalpe attract visitors from around the world, and the UNESCO recognition provides a new layer of protection and prestige.

Transhumance is far more than a simple journey. It is a living, breathing expression of the intricate relationship between humans, animals, and the mountains. It is a rhythm that has shaped the physical and cultural geography of the Alps, a tradition that continues to echo through its valleys, carried on the sound of a thousand chiming bells.