In our modern, climate-controlled world, it’s easy to take a cool room on a scorching day for granted. With the flick of a switch, we summon refrigerated air, creating a personal oasis insulated from the weather outside. But what if the building itself was the air conditioner? For millennia, before the hum of HVAC units became ubiquitous, humanity relied on a far more elegant and sustainable solution: architecture born from its environment. This is the world of vernacular architecture—structures built not by famous architects, but by local people using regional materials and time-tested wisdom to live in harmony with their specific geography.

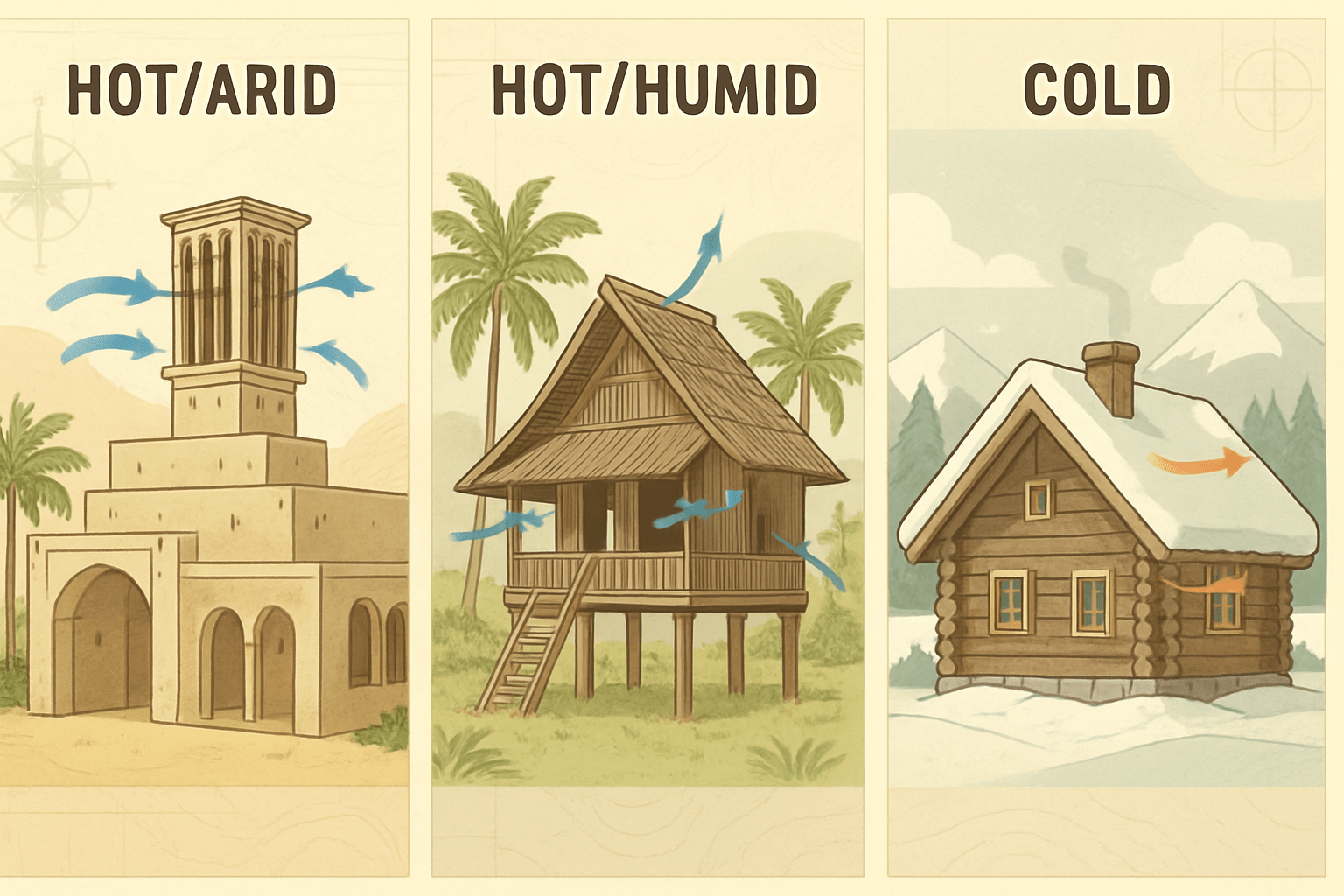

Vernacular design is a masterclass in climate-smart engineering, a physical library of human adaptation. It tells a story of place, of prevailing winds, solar angles, and seasonal rains. Let’s journey across the globe to explore three distinct geographical contexts and the architectural genius they inspired.

Beating the Heat with Earth: Adobe Homes of the American Southwest

Travel to the arid landscapes of New Mexico, Arizona, or southern Colorado, and you’ll find a geography of extremes. The sun is intense, rainfall is scarce, and the diurnal temperature range is vast—blistering hot days give way to surprisingly cool nights. This is the domain of the classic adobe home, a building form perfected by the Ancestral Puebloans and later adopted by Spanish settlers.

The secret lies in the very earth beneath their feet. Adobe bricks are a simple mixture of sand, clay, water, and a binding material like straw, formed in molds and baked hard by the desert sun. The key to their climate-resilience is thermal mass.

- A Natural Heat Sink: The thick, dense adobe walls (often several feet thick) act like a thermal battery. During the day, they slowly absorb the sun’s intense heat, preventing it from penetrating the interior. The inside of an adobe home remains remarkably cool, even at the peak of a summer afternoon.

- Nightly Radiance: As the desert air cools rapidly after sunset, the adobe walls begin to slowly release their stored heat back into the living space, providing a gentle, natural warmth throughout the cool night.

The design complements the material. Small, deeply set windows minimize direct solar gain while still allowing for light and ventilation. Flat roofs, common in these low-precipitation regions, could be used for collecting precious rainwater or even as an extra living or sleeping space on cool summer evenings. Structures like the Taos Pueblo in New Mexico, continuously inhabited for over 1,000 years, stand as a testament to the enduring genius of building with the land, not just on it.

Harnessing the Wind: Iran’s Ingenious Badgirs

Now, let’s journey to the hot, arid plains of the Iranian Plateau, to cities like Yazd, famously known as the “City of Windcatchers.” Here, the challenge is not just heat, but a stifling, stagnant air. The solution is an iconic and sophisticated piece of vernacular technology: the Badgir, or windcatcher.

A Badgir is a tall, chimney-like tower rising from the roof of a building, with openings at the top facing the prevailing winds. Its function, however, is far more complex than a simple window. It is a passive ventilation system that operates on two key geographical principles:

- Catching the Breeze: The tower’s primary function is to “catch” any wind high above the building and funnel it down into the rooms below. This creates a refreshing breeze, replacing the hot, still air inside.

- The Stack Effect: Even on a windless day, the Badgir works. The sun heats the air inside the tower, causing it to rise. This creates a pressure difference that sucks cooler air from the lower levels of the house up through the tower, generating a continuous, gentle airflow.

The most brilliant iterations of the Badgir were combined with another marvel of Persian geography: the qanat. A qanat is a gently sloping underground channel that taps into subterranean water tables, bringing cool water to the surface for irrigation and drinking. When a Badgir’s air shaft was connected to a qanat’s underground channel, it would pull air over the cool, running water. This process of evaporative cooling would chill the air before it even entered the home, creating a primitive but highly effective form of natural air conditioning. It’s a stunning example of integrating multiple geographical features—wind and groundwater—into a single, elegant architectural system.

Living with Water: The Elevated Houses of Southeast Asia

Our final stop takes us to the tropical monsoon climates of Southeast Asia, a region defined by high heat, intense humidity, and seasonal deluges. In countries like Thailand, Vietnam, Cambodia, and the Philippines, the primary geographical challenges are not just heat, but also flooding and moisture.

The architectural response is the stilt house, known by various local names like the Bahay Kubo in the Philippines or the traditional Thai house. By raising the entire living space off the ground on sturdy posts, these structures ingeniously solve multiple problems at once.

- Flood and Pest Protection: The most obvious benefit is safety. Elevation keeps the home and its inhabitants dry during the heavy rains of the monsoon season and protects them from the damp ground, as well as pests and wildlife.

- Enhanced Ventilation: The space beneath the house is not wasted; it’s a critical component of the cooling system. Air is free to circulate under the entire floor, drawing heat and moisture away from the living area above. This constant airflow provides significant relief from the oppressive humidity.

- Climate-Appropriate Materials: These homes are typically built from lightweight, local materials like bamboo, timber, and woven palm fronds or thatch for the roof. Unlike concrete or brick, these materials do not store large amounts of heat, allowing the structure to cool down quickly after the sun sets. Large, overhanging eaves provide ample shade and protection from frequent rain showers.

The stilt house is the embodiment of adaptation to a wet, tropical geography—a design that breathes, stays dry, and respects the powerful natural forces of its environment.

Lessons from the Past for a Sustainable Future

Adobe homes, Badgirs, and stilt houses are more than just historical curiosities. They are powerful reminders that for centuries, we built smarter, not harder. They represent a deep, intuitive understanding of place—a form of “passive design” that achieves comfort and resilience without consuming fossil fuels.

In an era of climate change and soaring energy costs, the wisdom embedded in vernacular architecture has never been more relevant. Modern architects and builders are increasingly looking to these traditional designs for inspiration, integrating principles like thermal mass, natural ventilation, and solar shading into contemporary buildings. By studying how our ancestors used the unique geography of their homelands to their advantage, we can rediscover a more sustainable, responsible, and geographically intelligent way to build our future.