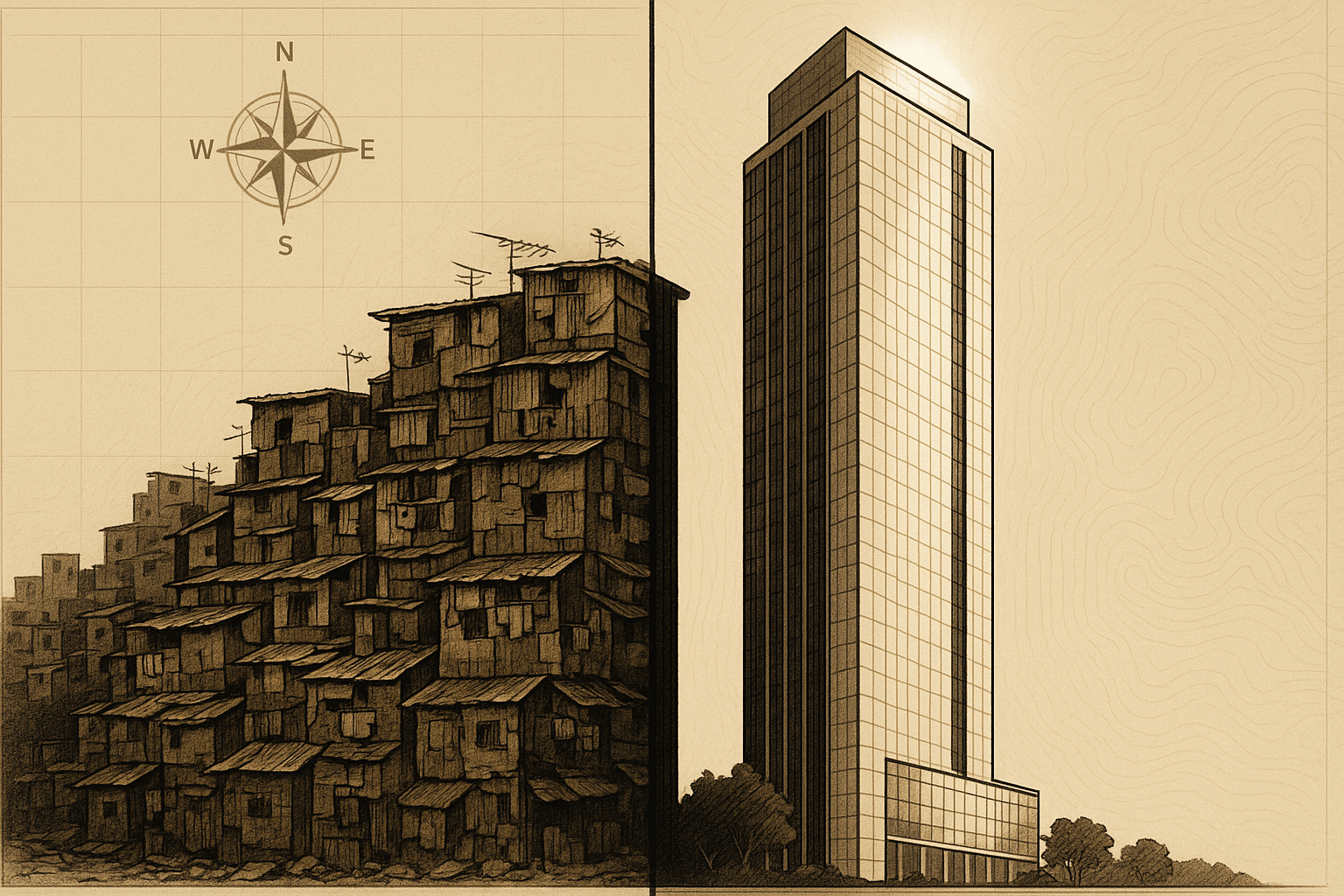

Look up at the skyline of a modern megacity, and you’ll see a story written in concrete, steel, and glass. For decades, we’ve marveled at the ambition of skyscrapers, viewing them as symbols of economic power and human ingenuity. But in sprawling urban centers like Mumbai or São Paulo, a new, more complex narrative is being etched into the sky. This is the story of vertical geography, a phenomenon where extreme wealth and desperate poverty don’t just exist in different neighborhoods—they exist on different floors, sharing the same vertical plane but separated by an unbridgeable social chasm.

Gleaming luxury towers with infinity pools and private helipads cast long shadows over densely packed, precarious structures that have also grown upwards out of necessity. These are the vertical slums, and their proximity to the penthouses of the elite creates one of the most visually jarring and socially significant landscapes of our time.

What is Vertical Geography?

When we think of geography, we often think horizontally—of maps, borders, and the distance between places. Vertical geography, however, introduces the Z-axis (height) as a critical dimension of social and physical space. In cities where land is impossibly scarce and expensive, the only direction to build is up. But this upward expansion is rarely equitable.

Vertical geography is the study of how height shapes human life in urban environments. It dictates access to fundamental resources: sunlight, clean air, and even safety. It creates new forms of segregation, where your floor number can be as significant as your street address in determining your social status, your health outcomes, and your daily experience of the city. In this new landscape, the sky itself is stratified, divided into layers of privilege and precarity.

Mumbai: A Skyline of Breathtaking Inequality

Nowhere is this vertical divide more apparent than in Mumbai, India. The city is a sliver of land crammed with over 20 million people, making it one of the densest places on Earth. Here, the horizontal geography has forced a dramatic vertical explosion.

On one end of the spectrum is Antilia, the infamous private residence of billionaire Mukesh Ambani. It’s not just an apartment; it’s a 27-story, 400,000-square-foot personal skyscraper in the heart of South Mumbai. It contains three helipads, a 168-car garage, multiple swimming pools, a ballroom, and requires a staff of around 600 to maintain. From its hanging gardens, the view is a panoramic sweep of the city and the Arabian Sea. Antilia is the ultimate expression of vertical dominance—a private kingdom in the sky.

Just a few miles away, and often visible from such towers, lies a contrasting reality. While slums like Dharavi are famous for their horizontal sprawl, the city is also filled with informal vertical settlements. These can be crumbling, century-old apartment blocks known as chawls, where entire families live in single rooms, or illegally constructed buildings that rise floor by precarious floor, built with scavenged materials and without architectural oversight. In these structures, lower floors are often dark, damp, and airless. Higher floors, while getting more light, might be structurally unsound, exposed to the elements, and a death-trap in case of a fire.

The most powerful image of Mumbai’s vertical geography is the photograph seen around the world: a luxury high-rise with pristine blue swimming pools on every balcony, directly overlooking a vast, sprawling slum. The residents of these two worlds share the same air, endure the same monsoon rains, and hear the same city noise, yet their lives are galaxies apart. The luxury tower offers a retreat from the city’s chaos; the slum below bears the brunt of it. This visual proximity doesn’t bridge the gap; it makes the inequality feel more acute, more visceral.

São Paulo: Fortified Heavens and Precarious Cortiços

Across the globe in São Paulo, Brazil, a similar story unfolds, albeit with its own unique characteristics. As one of the world’s great megacities, São Paulo has also raced skyward. The wealthy have retreated into what can only be described as vertical gated communities.

These luxury residential towers are fortresses in the sky, complete with high walls, 24/7 security, and amenities—pools, gyms, playgrounds, even private cinemas—designed to insulate residents from the perceived dangers of the city below. For the elite, the city is something to be viewed from a safe distance, from a balcony hundreds of feet in the air.

Meanwhile, the city’s poorest residents have found shelter in a different kind of tower: the cortiço vertical, or vertical slum. These are often abandoned downtown office or hotel buildings that have been occupied by hundreds, sometimes thousands, of squatters. Lacking formal ownership, the residents live in a state of constant uncertainty. The infrastructure is a patchwork of illegal electrical connections (known as gatos or “cats”), makeshift plumbing, and stairwells that have become vertical streets, bustling with life but also fraught with danger.

The tragic story of the Wilton Paes de Almeida building serves as a stark reminder of this precarity. A 24-story former police headquarters, it had been occupied by around 150 families. In 2018, a fire caused by a short circuit ripped through the building, causing it to collapse in a horrifying spectacle. The building wasn’t just a shelter; it was a vertical community, and its collapse was a physical manifestation of a systemic failure to provide safe housing for the urban poor.

The Geography of Air, Light, and Power

Ultimately, the contrast between luxury towers and vertical slums is a battle for the basics. In a dense city, these elements become positional goods—their value is determined by your location relative to others.

- Light and Air: In a luxury tower, height buys you clean air above the pollution line, unobstructed sunlight, and panoramic views. These are premium commodities. In a vertical slum, crammed next to other buildings, light and air are luxuries few can afford. The lower you are, the darker and more suffocating your environment.

- Access and Safety: A high-speed, air-conditioned elevator in a luxury tower whisks you to your climate-controlled apartment. In a cortiço, you might have to haul water and groceries up 20 flights of crumbling stairs. Safety is engineered into the luxury tower, while the vertical slum is a constant hazard of fire, structural failure, and crime.

- Power and Water: The elite have uninterrupted access to electricity and clean, pressurized water. The poor rely on illegal taps and carry water in buckets, living with the daily threat of disconnection or disaster.

The skyline, therefore, is more than just a collection of buildings. It is a physical map of social stratification. It shows us who has the power to rise above the city’s challenges and who is forced to live within them, stacked one on top of the other. As our world becomes increasingly urbanized, this vertical dimension of inequality will only become more important. It poses a fundamental question for urban planners, governments, and all of us: What kind of cities are we building when the divisions in our society are so clearly, and so dramatically, written in the sky?