The Map in Your Pocket Was Made by People Like You

The next time you pull out your phone to find the nearest coffee shop, navigate a new city, or check traffic, pause for a moment. Who made that map? For centuries, cartography was the exclusive domain of governments, armies, and powerful corporations. It was a top-down process, where experts with expensive equipment decided what was important enough to be put on the map. But a quiet revolution has been unfolding, one that puts the power of map-making into the hands of ordinary people. This is the world of Volunteered Geographic Information (VGI), and it’s changing not just how we see the world, but how we interact with it.

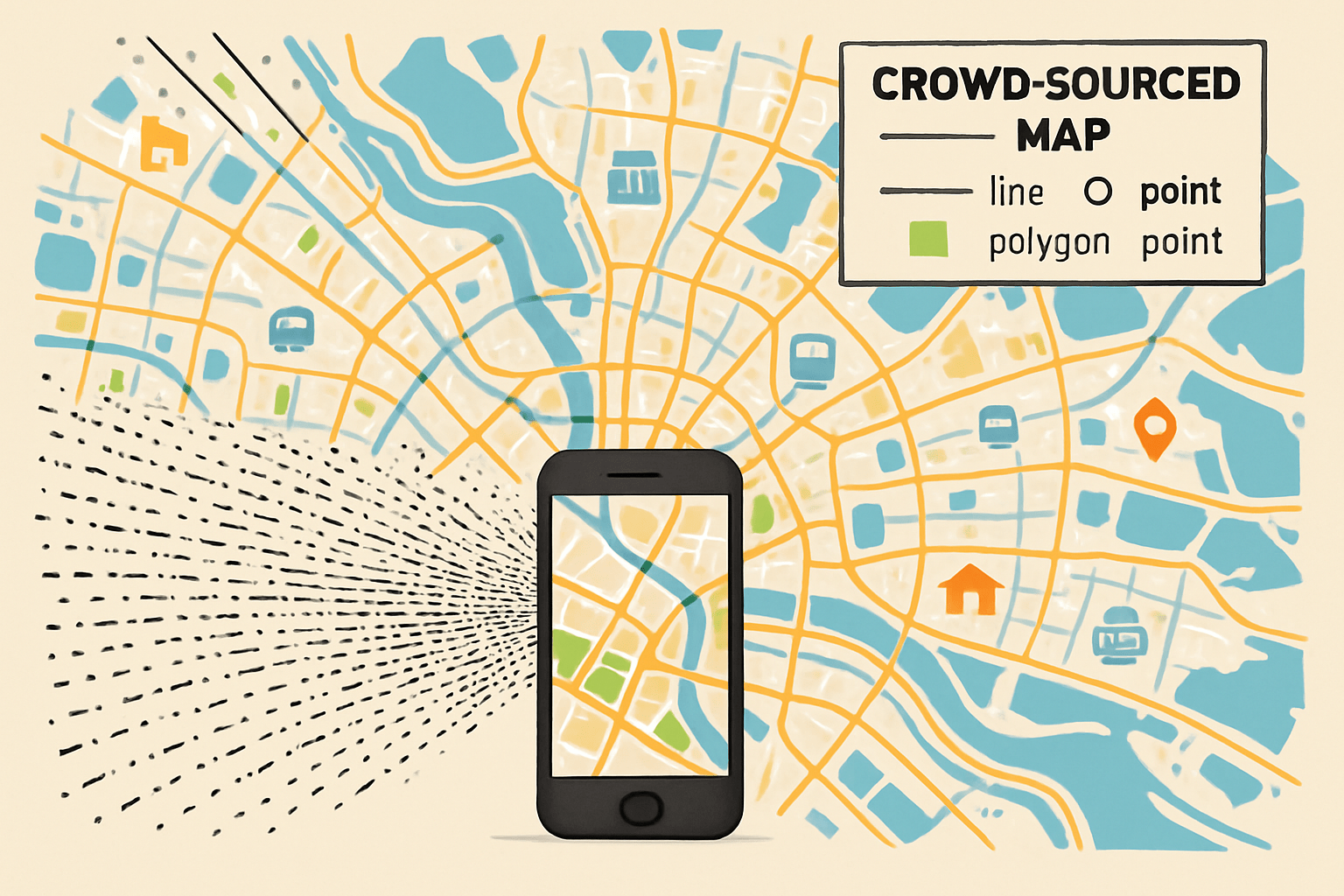

At its heart, VGI is geographic data created voluntarily by private citizens. Think of it as the crowdsourcing of the planet. Coined by geographer Michael Goodchild in 2007, the term captures a phenomenon powered by the convergence of several technologies: the GPS in our pockets, access to high-resolution satellite imagery, and the collaborative power of the internet. The undisputed king of the VGI world is OpenStreetMap (OSM), often called the “Wikipedia of maps.”

Founded in 2004 by Steve Coast, who was frustrated by the high cost and restrictions of official map data in the UK, OSM is a global project to create a free, open-source map of the entire world. Anyone, anywhere, can sign up and start contributing. You can trace roads from satellite images, add your local library, tag a park bench, or update a restaurant’s opening hours. This bottom-up approach creates a map that is not only vast but also incredibly rich in local, nuanced detail—the kind of information that a national agency might never capture.

Mapping When It Matters Most: VGI in Humanitarian Crises

The true power of VGI is never more apparent than in the chaotic aftermath of a disaster. When natural catastrophes strike, up-to-date maps are a life-or-death resource for first responders. They need to know which roads are blocked, where hospitals are located, and where displaced people are gathering. Unfortunately, official maps for many vulnerable regions are often outdated, incomplete, or non-existent.

This is where the citizen cartographers step in. The 2010 Haiti earthquake is the seminal case study. Port-au-Prince was a sprawling city, much of which was a “blank spot” on existing digital maps. Within hours of the quake, the Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team (HOT) activated a global network of volunteers. Using freely available satellite imagery taken after the earthquake, thousands of people from around the world began meticulously tracing roads, identifying damaged buildings, and mapping makeshift refugee camps.

The results were staggering. In a matter of days, volunteers created the most detailed and current map of Port-au-Prince in existence. This data was downloaded directly by aid workers on the ground, guiding search and rescue teams through the rubble and helping organizations like the Red Cross deliver critical supplies. This model has since been replicated countless times, from mapping the devastation of Typhoon Haiyan in the Philippines to supporting aid efforts during the Ebola outbreak in West Africa and providing logistical support in Ukraine.

A Challenge to Authority: The Democratization of Cartography

The rise of VGI inherently challenges the traditional authority of National Mapping Agencies (NMAs), like the Ordnance Survey in the UK or the U.S. Geological Survey. For generations, these institutions were the sole gatekeepers of geographic truth. Their maps were meticulously produced, highly accurate, and considered the official record. However, this process is also slow, expensive, and selective.

VGI offers a different paradigm:

- Speed and Timeliness: A new roundabout or shop can appear on OpenStreetMap within hours of its creation, whereas an official map update might take months or years.

- Local Knowledge: VGI excels at capturing what geographers call “semantic richness.” An official map might show a building, but OSM contributors can add that it’s a bakery, its name, its opening hours, and whether it has wheelchair access. It maps what matters to people on the ground.

- Mapping the Unmapped: VGI gives visibility to places often ignored by official cartography, such as informal settlements or slums. Projects like Map Kibera in Nairobi have empowered residents to put their own community on the map, literally, enabling them to advocate for better services and infrastructure.

This isn’t to say VGI is replacing official data. Instead, a fascinating synergy is developing. Many official bodies now incorporate OSM data into their products, and some even contribute their own data back to the project. The “cartographic conversation” is no longer a monologue from on high; it’s a dynamic, collaborative dialogue.

But Is It Accurate? The Lingering Question of Data Quality

The most common criticism leveled at VGI is predictable: if anyone can edit it, can we really trust it? It’s a valid concern. Unlike an official map, there is no central authority guaranteeing the accuracy of every single data point in OpenStreetMap.

However, the VGI community relies on a principle similar to “Linus’s Law” from the open-source software world: “Given enough eyeballs, all bugs are shallow.” The idea is that with a large and active community, errors are quickly spotted and corrected by other users. Research has repeatedly shown that in well-mapped areas (like major cities in Europe and North America), the positional accuracy and completeness of OSM data can rival, and sometimes exceed, that of official sources.

Data quality in VGI is not a simple “good” or “bad” metric. It’s more useful to think of it as “fitness for purpose.”

- Positional Accuracy: Is a road in the correct geographic location? This is often very high.

- Completeness: Are all the roads and buildings mapped? This varies hugely. London is incredibly detailed, while a remote rural village in Siberia may be less so.

- Attribute Accuracy: Is a street’s name spelled correctly? Is the speed limit right? This depends on the diligence of local contributors.

For a humanitarian worker needing a navigable route through a disaster zone, an 80% complete map that is available now is infinitely more valuable than a 100% perfect map that will be ready in six months. The context determines the value.

The Future is Mapped by Us

Volunteered Geographic Information has fundamentally altered our relationship with the world and its representation. It has transformed cartography from a professional lecture into a global conversation. By empowering citizens to map their own communities, VGI fosters local engagement, provides critical data in times of crisis, and fills the vast blank spaces left by traditional map-makers.

The line between the “volunteer” and the “professional” is blurring, creating a richer, more dynamic, and more democratic geographic landscape. So the next time you use a map, remember the global community of volunteers behind it—the citizen cartographers who are, piece by piece, building a map of the world, for the world.