Ever take a road trip through the countryside and notice a peculiar rhythm to the landscape? A major city gives way to a ring of smaller towns, which in turn are surrounded by even smaller villages and hamlets. Then, the pattern repeats itself in the distance. It feels organized, almost designed. You might think it’s a coincidence, but it’s not. There’s an invisible economic logic at play, a concept that beautifully explains this predictable spacing: Central Place Theory.

This powerful idea, a cornerstone of AP Human Geography, was developed in the 1930s by a German geographer named Walter Christaller. He was fascinated by the seemingly orderly pattern of towns in Southern Germany and set out to create a model that could explain it. What he discovered was that the location, size, and spacing of settlements aren’t random at all; they’re driven by simple economics.

The Core Idea: Central Places and Their Hinterlands

At its heart, Central Place Theory is simple. It proposes that settlements emerge to function as “central places”—hubs that provide goods and services to the surrounding population. This surrounding area, which depends on the central place for its needs, is called the hinterland or market area.

Think of a large city. It offers everything from international airports to specialized medical care. The people living in the city use these services, but so do people from dozens of smaller towns in the surrounding region. That city is the central place, and the entire region it serves is its hinterland.

But why aren’t all towns giant cities? Christaller explained this with two brilliant, interconnected concepts: threshold and range.

The Economics of Your Errand Run: Threshold and Range

Everything about where you shop and how far you’re willing to go for it can be explained by these two ideas. They are the engine that drives the entire theory.

Threshold: How Many Customers Do You Need?

The threshold of a good or service is the minimum number of people needed to support it. In other words, how many potential customers does a business need to stay afloat?

- A corner convenience store has a very low threshold. It only needs a few hundred people in a neighborhood to buy milk, bread, and snacks to make a profit.

- A neurosurgery clinic, however, has a very high threshold. It needs a massive population base (hundreds of thousands, if not millions) to find enough patients who require its highly specialized services.

This is why you find convenience stores and gas stations in almost every tiny settlement, but you’ll only find a brain surgeon in a major metropolitan area.

Range: How Far Will You Go?

The range of a good or service is the maximum distance people are willing to travel to obtain it. Like threshold, this also varies dramatically.

- For a gallon of milk (a “low-order good”), your range is probably very small—a few blocks or maybe a mile. You wouldn’t drive 50 miles just for milk.

- For a brand-new car or a wedding dress (a “high-order good”), your range is much larger. You might be willing to travel an hour or more to a larger city to get the exact model or style you want.

- For a world-class university or a professional sports team, the range can be national or even international!

A Ladder of Settlements: Building the Hierarchy

When you combine threshold and range, a natural hierarchy of settlements emerges.

- Hamlets: At the very bottom are the smallest settlements. They only offer basic, low-order goods like a gas station or a small post office. These services have a low threshold and a short range, so you need many small hamlets spread out to serve the rural population.

- Villages: A bit larger, a village can support services with a slightly higher threshold, like a primary school, a doctor’s office, and a small grocery store.

- Towns: Towns are larger still. They have everything a village has, plus higher-order services like a high school, a supermarket, a hospital, and a movie theater. They serve the people in the town itself and those in the surrounding villages and hamlets.

- Cities: At the top are cities, the largest central places. They offer the most specialized, high-order goods and services: universities, major sports stadiums, large airports, luxury goods retailers, and specialized corporate headquarters. A city has a huge hinterland, encompassing all the towns and villages around it.

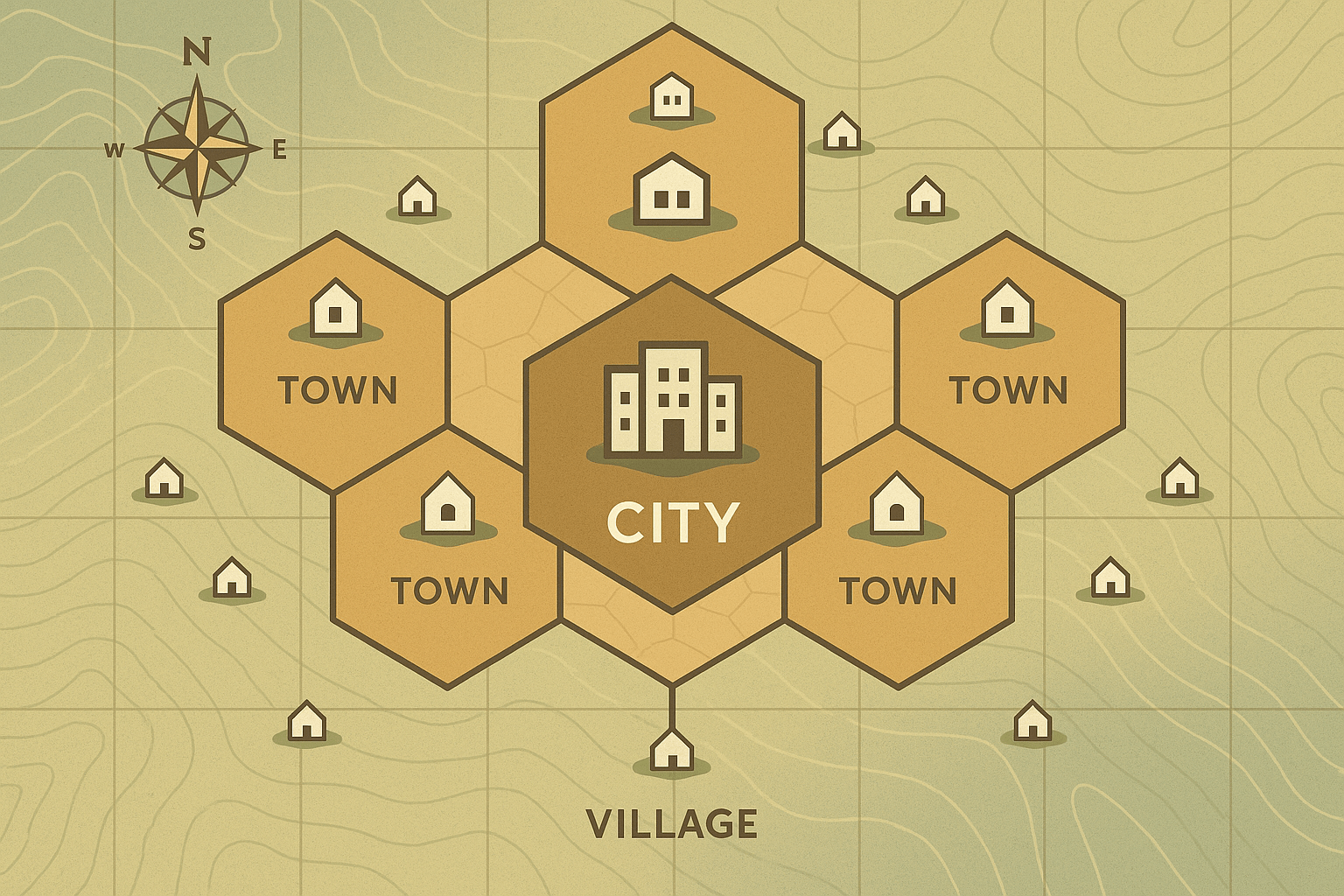

This creates a predictable pattern: a few large cities, surrounded by a greater number of medium-sized towns, which are in turn surrounded by a multitude of small villages.

The Geometry of Geography: Why Hexagons?

So we have the logic, but what about the map? Christaller wanted to represent this hierarchy visually. He first considered using circles to draw the market areas around each central place. But circles have a problem: if you pack them together, they either overlap (meaning businesses are competing for the same customers) or leave unserved gaps in between.

Christaller’s elegant solution was the hexagon. Hexagons fit together perfectly, like a honeycomb. They tile a surface with no gaps and no overlap. This makes them the most efficient shape for modeling market areas in theory. In a perfect Christaller model, the landscape would look like a neat, nested honeycomb of hexagons, with the highest-order city at the center of the largest hexagon, and smaller towns and villages at the corners of progressively smaller hexagons.

Reality Check: When the Model Meets the Real World

Of course, if you look at a real map, you won’t see a perfect geometric pattern of hexagons. Christaller’s theory is a model, and to work, it had to make some big assumptions:

- The land is a flat, featureless plain (what geographers call an “isotropic plain”).

- The population and purchasing power are evenly distributed.

- People are rational and will always travel to the closest central place for a service.

- All transportation is equally easy in every direction.

The real world, as we know, is messy. Physical geography plays a huge role; mountains, rivers, and coastlines dictate where people settle and how they travel. Transportation infrastructure, like highways and railways, creates corridors of development, pulling settlements into linear patterns. Furthermore, history, culture, and politics influence where cities are founded and grow. And today, the internet throws a whole new wrench in the works, making the concept of “range” for many goods almost limitless.

The Invisible Logic of Our Landscape

Despite its limitations, Central Place Theory remains a profoundly useful tool. It gives us a framework for understanding the invisible economic forces that shape our visible world. It explains why you can’t buy a Lamborghini in a town of 500 people, and why big cities become powerful economic engines for vast regions.

The next time you’re on a long drive, watching the towns appear and fade on the horizon, remember Walter Christaller. You’re not just seeing random dots on a map; you’re witnessing a beautiful, logical hierarchy that connects every small town to the biggest city, all driven by the simple question: “How far are you willing to go for a gallon of milk?”