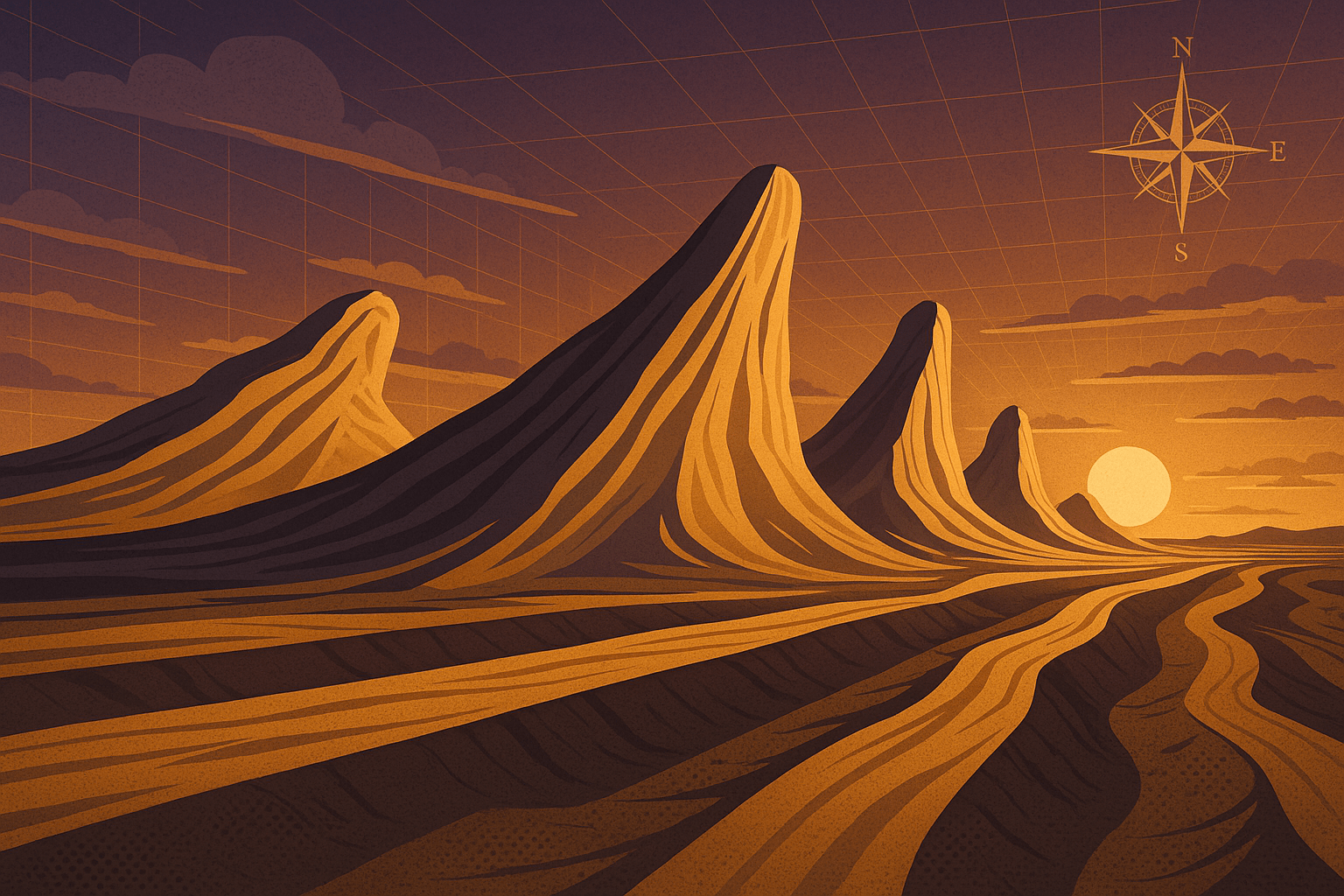

Imagine sailing across a vast, ochre-colored sea, not on water, but on land. The vessels are not made of wood and canvas, but of ancient rock, their hulls streamlined and pointing into the wind. This isn’t a science fiction novel; it’s a journey into the heart of some of Earth’s—and Mars’s—most extreme deserts. Welcome to the world of yardangs.

These colossal, wind-sculpted ridges are one of physical geography’s most dramatic phenomena. Rising from flat desert plains like a fleet of petrified ships, they are a powerful testament to the patient, persistent artistry of wind. Let’s explore how these geological marvels are formed, where you can find them, and why they are a crucial clue in our exploration of the Red Planet.

What Exactly is a Yardang?

The term “yardang” comes from the Turkic language of Central Asia, meaning “steep bank” or “ridge.” It was introduced to the English-speaking world by the Swedish explorer Sven Hedin in the early 20th century after his travels in the Gobi Desert. The name perfectly captures their essence: yardangs are elongated, streamlined rock formations carved from bedrock or semi-consolidated material by the abrasive action of wind-blown sand.

Their shape is their most defining characteristic. They are typically much longer than they are wide, with a blunt, steep face pointing upwind (the “prow”) and a tapering “tail” that points downwind. This aerodynamic form, often compared to the inverted hull of a boat, is the direct result of erosion by a dominant, unidirectional wind. Their scale can vary dramatically, from small features a few meters long to mega-yardangs that stretch for several kilometers and stand over 100 meters tall.

The Art of Wind: How Yardangs are Formed

Yardangs are not built, but revealed. They are the remnants of a landscape slowly stripped away by one of nature’s most relentless forces. The process requires a specific set of ingredients:

- A dry, arid environment with little to no vegetation to hold the soil in place.

- A supply of abrasive particles, typically sand or silt.

- Strong, persistent winds that blow consistently from one direction over geological timescales.

- A suitable rock type, often composed of alternating layers of hard and soft sedimentary rock.

The formation involves two key aeolian (wind-related) processes:

Deflation: This is the first step, where the wind acts like a giant broom, lifting and removing loose, fine-grained particles from the desert floor. It sweeps away the unconsolidated sediment, lowering the overall ground level and exposing the more resistant bedrock beneath.

Abrasion: This is the sculpting process. The sand and silt particles carried by the wind become a powerful sandblasting tool. As this natural sandpaper scours the exposed rock, it exploits weaknesses. Softer rock layers are eroded much faster than harder, more resistant layers. The wind carves grooves and channels into the landscape, leaving the tougher rock behind as elongated ridges. Over thousands to millions of years, these ridges are streamlined into the classic yardang shape we see today.

A Global Tour of Earth’s Yardangs

While found in arid regions worldwide, some locations host truly spectacular yardang fields that create otherworldly landscapes.

The Lut Desert, Iran

Perhaps the most famous and visually stunning collection of yardangs on Earth is found in Iran’s Lut Desert. Known locally as the “Kaluts”, these mega-yardangs form a breathtaking desert city of sand and rock. Stretching over an area of 80 by 120 kilometers, they create a maze of natural corridors and towering ridges. The sheer scale and perfection of their form led UNESCO to designate the region as a World Heritage site, recognizing it as an exceptional example of ongoing geological processes.

The Gobi Desert, China and Mongolia

This is the region that gave yardangs their name. The vast, windswept plains of the Gobi are dotted with these formations, particularly in the Dunhuang area of China. For centuries, these natural sculptures have guided and intimidated travelers along the ancient Silk Road. Their presence speaks to the harsh, hyper-arid conditions that have dominated this part of Central Asia for millennia.

The Atacama Desert, Chile and Peru

As one of the driest places on the planet, the Atacama is a prime location for aeolian landforms. In southern Peru, near the Paracas National Reserve, and in parts of northern Chile, extensive yardang fields have been carved from ancient lakebed sediments and volcanic ash deposits. The stark, alien beauty of these landscapes has not been lost on filmmakers, who often use the Atacama as a stand-in for other planets.

Egypt’s Western Desert

The desert west of the Nile River, particularly around the Kharga Oasis, is home to classic yardangs. Here, they are carved from chalky limestone and stand as white “ships” in a sea of yellow sand. These formations are a reminder that the Sahara is not just endless dunes but a geologically diverse landscape shaped by both wind and the memory of a wetter past.

Land Ships on the Red Planet: Yardangs on Mars

Fascinatingly, some of the best-studied yardangs aren’t on Earth at all. Mars, with its thin atmosphere, powerful winds, and vast, dry surface, is a perfect factory for yardang production. They were first identified by the Mariner 9 orbiter in the 1970s and have since been studied in detail by orbiters like the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter and rovers like Curiosity and Perseverance.

On Mars, yardangs are more than just a geological curiosity; they are a critical scientific tool:

- Fossil Wind Vanes: Because their orientation is dictated by the prevailing wind, Martian yardangs act as giant weather vanes frozen in time. By mapping their direction across the planet, scientists can reconstruct ancient global wind patterns, providing insights into the Red Planet’s past climate.

- Clues to Past Water: Many Martian yardangs, especially those in the Medusae Fossae Formation, appear to be carved from easily eroded materials like compressed volcanic ash or, more tantalizingly, ancient lakebed or seabed sediments. The very existence of these yardangs can point rovers toward areas that may once have been habitable, preserving the story of a wetter, more dynamic Mars.

- Gauging Erosion: By studying how quickly yardangs are being formed or eroded today, scientists can measure the current power of Martian winds and understand the ongoing processes that are shaping its surface.

A Testament to Wind’s Power

From the scorching plains of the Lut Desert to the frozen craters of Mars, yardangs are a profound illustration of how a seemingly gentle force like the wind can, with enough time, sculpt entire landscapes. They are monuments of erosion, streamlined and aligned as if by an artist’s hand. These land ships, sailing silently on seas of sand, not only create some of the most surreal and beautiful scenery on our planet but also hold vital clues to the climate and history of another.